Ankle Injury Prevention Methods and Principles

by: Nicholas C. Mang, SPT

Background:

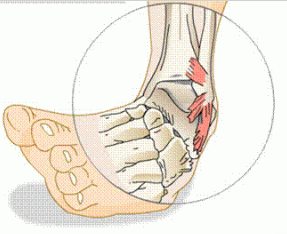

The motivation behind this capstone project was fueled by my desire to reduce the incidence of lateral ankle sprain in the general public and in athletes. I recognized the opportunity to incorporate preventative healthcare concepts in the form of ankle injury prevention by collaborating with and educating members of UNC’s wellness community. I set out to identify the best evidence regarding ankle injury risk factors and injury prevention strategies in order to address an evident problem in our society. The term “ankle sprain” may sound benign, but it is one of the most common injuries incurred by athletes in the United States resulting in loss of function and loss of play time.1 Lateral ankle sprains are not only one of the most common injuries in sports that demand jumping, landing, and cutting maneuvers, but they also result in considerable direct and indirect healthcare expenditures.2 It is estimated 1 million (15%) high school basketball and soccer players sustain an ankle sprain each year.2 Furthermore, McGuine and Keene report the average direct healthcare costs associated with ankle sprain for high school basketball and soccer players is $70 million, and indirect costs mount to $1.1 billion.2 One must keep in mind that these numbers do not account for any other sport or competitive level. In addition to the societal and financial costs, ankle sprains can have a major impact on one’s physical and psychoemotional well being. Additional musculoskeletal issues may include tendinopathies and tears, ankle impingement, ankle synovitis, chronic ankle instability, and ankle osteoarthritis.3 The quality of life associated with ankle osteoarthritis is reported to be equal to or worse than congestive heart failure, end-stage kidney disease, and cervical-spine pain/radiculopathy.4 Therefore, I viewed this project as an excellent opportunity to promote a preventative care strategy that might lead to decreased financial, functional, and psychoemotional costs associated with ankle sprain injury.

Project:

I desired to enhance interdisciplinary collaboration between those in the physical therapy profession and in other disciplines. One outcome product included a live evidence-based presentation for members of UNC’s wellness community (e.g., personal trainers, massage therapists, sports coaches) to improve identification of clientele who are at increased risk for ankle injury, and to provide recommendations for supposed clientele. In Evidence-Based Practice II, I critically appraised best evidence regarding the effect of prophylactic lace-up ankle brace use on the incidence/risk of ankle sprain in basketball players. I used this literature review as a “springboard” for all capstone project outcome products. I engaged in further appraisal of the literature regarding ankle injury risk factors, prophylactic ankle brace use for injury prevention, the effect of balance/proprioceptive exercises on ankle injury risk reduction, and the impact of sport-specific warm-up on ankle injury reduction. In addition to the live presentation at UNC Wellness Center—Northwest Cary, outcome products included a brochure for individuals who have sustained a previous ankle sprain; an evidence table addressing ankle injury risk factors, the prophylactic use of ankle braces, the use of balance/proprioceptive training, and functional warm-up on ankle injury risk reduction; and the construction of wobble boards used for balance exercises.

Findings:

The most relevant ankle sprain risk factors are previous ankle sprain5; non-use of ankle brace or taping1,6; air cell in the heel of shoe; balance deficits; no pre-activity stretching; tight gastrocnemius; and sports requiring vigorous jumping, landing, and cutting maneuvers.

The evidence supports the use of external ankle support in the form of ankle bracing. Ankle brace usage during sporting activities is found to decrease the risk of ankle sprains in individuals who have and have not sustained a previous ankle sprain. In more recent studies, researchers explore the impact of prophylactic ankle bracing using lace-up ankle braces, while older studies explored the impact of semi-rigid ankle braces. Several studies show that individuals who do not use ankle braces are 2-3 times more likely to incur an ankle sprain than those who do wear a lace-up ankle brace.1,6 According to researchers who have compared the benefits of ankle bracing versus ankle taping, both interventions seem to have protective benefits, but ankle taping appears to lose its protective qualities during a session of sporting activity and may lead to a greater number of complaints in regards to skin complications.7,8 Furthermore, a cost-benefit analysis revealed that lace-up ankle braces are more cost-effective than ankle taping over the course of a sports season.9 I have heard the argument that the use of ankle braces causes muscle weakness around the ankle joint. However, I did not identify any evidence suggesting that ankle braces lead to greater ankle musculature weakness.

The use of balance training appears to be effective in reducing risk of ankle sprain in multiple studies. However, balance training seems to be more effective in preventing ankle sprains in those with a history of ankle sprain than those with no history of ankle sprain.2,10

Neuromuscular warm-up appears to reduce the total number of injuries in athletes. However, the impact of neuromuscular warm-up does not appear to reduce the incidence of ankle sprain, alone. Compliance with warm-up programs seemed to be an issue in several of the studies included in the evidence table. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the true impact of a warm-up program on ankle injury reduction.

Collaboration:

I was privileged to have committee-member input on the appropriateness of educational materials. I consulted with UNC Wellness Center’s Lifestyle Enhancement Director and Physical Therapy Clinic Director to determine the educational and occupational backgrounds of intended audience members. I was constructively challenged in creating a PowerPoint presentation for a diverse audience consisting of personal trainers, massage therapists, group fitness instructors, and a lacrosse coach. Physical therapists and other wellness center staff were invited, but there were no additional attendees. I encouraged audience participation with ankle anatomy palpation, balance exercise activities and progressions, and discussion. Participants were encouraged to create balance exercise variations using a variety of ground surfaces (e.g., carpeted flooring and foam pad) and equipment (e.g., stability ball, wobble boards, bosu ball, resistance bands, and balls) following the didactic portion of the presentation.

I have made a career goal of engaging in strong interdisciplinary collaboration. This capstone project enabled me to engage in professional development. I was privileged with the amazing opportunity in educating and collaborating with others in the healthcare and wellness communities.

Evaluation:

I created an audience feedback form to help identify strengths and weaknesses associated with presentation layout, presentation delivery, and other educational materials. Feedback analysis revealed positive feedback with few additional comments. Additional comments included suggestions for optimizing the speed of presentation delivery (i.e., “slow down”) and optimizing public speaking skills (i.e. elimination of “uhs” and “umms”). Audience members reported satisfaction with the “question-and-answer” portion of the presentation, “good” application of “humor”, and general satisfaction with the learning experience.

I utilized verbal and written committee-member feedback for improving project elements, as well as recommendations for improving my confidence as a speaker and educator. In addition to incorporating committee feedback, I used Plack and Driscoll’s “Chapter 5: Design Concepts” in order to develop an appropriate PowerPoint presentation.11 Also, I used Microsoft Word’s “Readability Statistics” function to determine appropriateness of printed materials for clientele who have sustained previous ankle sprains. The Fleish-Kincaid Grade Level Score was determined to be 10.4 (10th grade), which was deemed appropriate for the majority of those who would be reading the brochure.

Acknowledgments:

Kathy DeBlasio, MA, FMFA, ATC, LAT, CPT, UNC Wellness Center’s Lifestyle Enhancement Director, provided insight into the educational and professional backgrounds of the wellness staff members who would be attending my presentation. Kathy supplied me with helpful information regarding collaboration between physical therapists and other UNC Wellness staff members. Kathy orchestrated the logistics and venue for my presentation. Thank you so very much, Kathy.

Pete Olmos,MPT, Meadowmont Physical Therapy Clinic Coordinator, provided helpful insight and advice for my outcome products. Pete, too, helped guide me in making the presentation most appropriate for the intended audience. Thank you, Pete.

Mike Gross, PT, PhD, FAPTA, was an excellent project advisor whom supplied extremely helpful information and resources for me. Mike’s knowledge of the foot and ankle is quite astonishing. I am forever grateful for the knowledge Mike Gross imparted throughout this project and my graduate school experience. Thank you, Mike

Mike McMorris, PT, DPT, OCS, Karen McCulloch, PT, PhD, NCS, provided great insight into the application of the capstone project, and assisted me with presentation logistics. Thanks so much, Mike and Karen.

Prue Plummer, PhD, provided excellent feedback on my initial literature search and review on prophylactic use of ankle braces in basketball players during the Evidence Based Practice-II class during the Fall 2014 semester. Thank you, Prue.

Pat McNamara and Anthony Bowman assisted with photography. Heather Eustis provided the power tools needed for the construction of the balance boards. Thank you!

References:

- McGuine T a, Brooks A, Hetzel S. The Effect of Lace-up Ankle Braces on Injury Rates in High School Basketball Players. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1840–1848. doi:10.1177/0363546511406242.

- McGuine T a, Keene JS. The effect of a balance training program on the risk of ankle sprains in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1103–1111. doi:0363546505284191 [pii].

- Herb CC, Hertel J. Current concepts on the pathophysiology and management of recurrent ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Reports. 2014;2:25–34. doi:10.1007/s40141-013-0041-y.

- Rao S, Ellis SJ, Deland JT, Hillstrom H. Nonmedicinal therapy in the management of ankle arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22(2):223–228. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e328335fceb.

- McKay GD, Goldie PA, Payne WR, Oakes BW. Ankle injuries in basketball: injury rate and risk factors. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(2):103–108. Available at: https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=c8h&AN=2001084601&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- McGuine T a., Hetzel S, Wilson J, Brooks a. The Effect of Lace-up Ankle Braces on Injury Rates in High School Football Players. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:49–57. doi:10.1177/0363546511422332.

- Hubbard TJ, Cordova M. Effect of ankle taping on mechanical laxity in chronic ankle instability. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2010;31(6):499–504. doi:10.3113/FAI.2010.0499.

- Lardenoye S, Theunissen E, Cleffken B, Brink PR, de Bie R a, Poeze M. The effect of taping versus semi-rigid bracing on patient outcome and satisfaction in ankle sprains: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):81. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-81.

- Mickel TJ, Bottoni CR, Tsuji G, Chang K, Baum L, Tokushige KAS. Prophylactic Bracing Versus Taping for the Prevention of Ankle Sprains in High School Athletes: A Prospective, Randomized Trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2006;45(6):360–365. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2006.09.005.

- Emery C a., Cassidy JD, Klassen TP, Rosychuk RJ, Rowe BH. Effectiveness of a home-based balance-training program in reducing sports-related injuries among healthy adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Cmaj. 2005;172(6):749–754. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040805.

- Plack M, Driscoll M. Design Considerations. In: Teaching and Learning in Physical Therapy: From Classroom to Clinic. SLACK Incorporated; 2011.

12 Responses to “Ankle Injury Prevention Methods and Principles”

Caitlin Gallagher

Nick-

I am very impressed with your capstone project! I loved how you reached out to involve other disciplines in order to improve collaborative care in the community. I wish I had been able to attend your presentation, but I am grateful that I can review all your hard work on this website. I had heard a few months ago that your project was related to lateral ankle sprains, and I had been looking forward to reviewing all your hard work, as this is a topic that really interests me! I was particularly interested in the information related to balance training and how it may reduce the risk of injury. Given my interest in this topic, I foresee myself referring back to this information (and you) in the future! Fantastic job.

Caitlin

Nicholas Mang

Caitlin,

I definitely wanted to incorporate a collaborative care component in my capstone, and I was really happy with how it all worked out. Thank you so much for looking at my products, Caitlin. I look forward to keeping up with you. Thanks, again.

– Nick

Jayson Hull

Nick I really enjoyed going over your capstone, you brought out some great points, and answered almost all the questions I had about ankle sprains, rehabilitation, and prevention. The information on lace-up ankle braces and their effectives in preventing ankle sprains was interesting. With this evidence out there, I wonder if whole teams will start to instruct players to ankle braces, similar to prophylactic knee braces for football lineman. Interestingly, I don’t believe the research fully supports the use of the prophylactic knee braces. Additionally, its nice to see conclusive evidence that the use of prophylactic ankle braces won’t contribute to a weaker ankle. I really enjoyed the slides in your presentation on the progressive balance training during the rehabilitation process. I found your educational handout very helpful, the lay out was visually appealing and the use of bullet points and pictures made it simple, quick, and informative. Great job Nick, your products will definitely be useful to anyone works with athletes or active adults.

Nicholas Mang

Hey Jayson,

Thanks so much for looking at my materials. You always provide great encouragement. I wish you the best.

-Nick

michael gross

Nick- one last thing. Do not refer to yourself in this product as “the student”. You should say that “I” …..

Mike

Nicholas Mang

Thanks, Mike. I made that change.

– Nick

Michael Gross

Nick- You really did a great job on all fronts for this project, but I am not surprised. The evidence table was strong and the presentation did a very nice job reaching out to the target audience to explain and help identify risk factors in the clients served by personal trainers. The brochure was informative and you displayed excellent carpentry skills with the wobble board construction. An excellent all-round job. Best regards, Mike Gross

Nicholas Mang

Mike,

Thank you so much for the feedback and being an excellent advisor. I developed a great love for the foot and ankle because of your material in MSK II. I have truly enjoyed learning more about the foot and ankle through this project. Again, thank you, Mike.

-Nick

Chris Ball

Nick,

Excellent work buddy! I thought you did a good job with developing a clear and understandable brochure for those at risk or post lateral ankle sprain with alternate importance of early PT intervention as well as methods of independent conservative maintenance. Additionally I am going to make myself a wobble board for personal use as well as a good example to present to patients as indicated so thank you profusely for your efforts in providing instruction to do so.

You present very interesting figures which are startling and put the scope of problem into perspective. Additionally you did a great job of clearly presenting the financial, functional and psychoemotional costs of ankle sprain injury such as the incidence of lateral ankle sprains in high school athletes costing up to 1.1 billion dollars indirectly, acute injury cost of greater than $ 3000.00 dollars per ER visit due to sprain and comparisons with other prevalent chronic disease conditions regarding lateral ankle sprains negative affect on quality of life.

The information you presented regarding decreased risk of ankle sprain with use of external bracing for those who have not suffered previous sprains as well as the benefit of using lace-up ankle braces compared to air-cast stirrup due to greater resistance/control of motions that drive lateral ankle sprains is critical for the interdisciplinary population you were attempting to reach and educate.

I thought it was great you highlighted the use of multi sensory challenges to balance training such as dynamic movement, closing the eyes, stressing postural muscles and the use of neuromuscular warm up and balance training with having large efficacy with treatment and preventing re-injury in those who have prior history of ankle sprain. Additionally, pairing this information with the actual 5-phase rehabilitation program adapted from Mcguire and Keene as well as warmup progression from Olsen et al also helps ensure implementation of such protocols following your presentation.

I thought it was very important that you also mention in your findings the lack of current evidence regarding the use of ankle bracing with causing decreased functional stability which i feel is a common belief among therapists and other health and wellness professionals. I thought it was an excellent idea to encourage hands on participation and input regarding the use and creation of balance exercise variations as to provide an optimal continuing education experience and ability to learn from one another in a collaborative manner. I thought it was very important that you point out the multiple joint articulations present at the ankle rather than one which allow normal efficient functional mobility and ambulation. For myself I thought the visuals you present of the ankle and its muscle-tendon units provided a great refresher on the layering and orientation with assessment and palpation the muscle tendon units as the course around the bony pulleys of the medial and lateral malleoli.

Transition of positive outcomes we achieve in PT once patients are DC is a major problem today and projects like this will surely promote and facilitate greater continuity of care and concept regarding pathomechanics of the foot/ankle articulations and their relationship to injury predisposition, their occurrence and methods of treatment will ensure long-term maintenance and prevention of re-injury in the future. As I said in another comment, between your and Mark’s capstone I feel optimally prepared to go into my final clinical rotation armed with the knowledge and tools to provide care of the upmost quality regarding injury and pathologies common to the foot and ankle.

Great work Nick, your inquisitive nature and thoroughness along with your overall respectful, genuine and kind nature is going to serve you well in becoming an excellent PT. True story, we were placed in the same interview groups long ago and after getting to interact and chat with you though the course of that stressful day I got home and told my mother that “If I didnt get in to UNC’s DPT program then I hoped you did because that’s the personality I would want from my therapist”

Much Love,

Chris

Nicholas Mang

Chris,

I cannot thank you enough for the time you put into reviewing my capstone products. I can definitely tell that you took a thorough look at all the materials. I am so thankful that both of us made it into UNC’s DPT program! 🙂 Thanks for being a great friend. I look forward to calling you my “colleague.”

-Nick

Michael Irr

Hi Nick,

Great job on your Capstone! I found your presentation to be very interesting and I wish I could have been there for the live version. The progression of the presentation was great and I thought the information on prevention programming was fantastic. You did a great job explaining the different exercises and progressions. The brochure was a great way to bring all of the information together and was easy to read. I remember you showing me the balance boards you made last time I was in Chapel Hill – awesome work on those! The quality was so good I have no doubt you could sell them.

I’m glad you addressed the argument that use of ankle braces can cause muscle weakness. This belief is very prevalent amongst many strength & conditioning coaches I have worked with in my career. My question regarding this subject: for an athlete, do you think there is a possibility of weakness from consistent bracing or is there simply no evidence at this point? I’m curious of your overall opinion.

Another topic in rehab I’ve heard discussed is the type of surface a person should engage in balance training. Many have advised an unstable surface – like a wobble board or foam bad. On the other hand, I’ve heard some advise balance training is better done on a stable flat surface (the ground), with perturbations or forces being applied to the body from “top-down”, which they claim would be more sport-specific. You touched on this in your presentation a little bit, but do you think one is better than the other, or should we focus on one more than the other during certain points of rehab?

Lastly, I did my capstone on ACL injuries and there is a lot of talk about contact vs non-contact mechanisms of injury. With research regarding ankle sprains, do they differentiate between the two? Is there a higher incidence of one or the other?

Again, great job with your Capstone project! You did some amazing work on it!

Take care,

Mike

Nicholas Mang

Mike,

Thank you so much for those encouraging words and excellent questions! I really appreciate it. Yes, there is an allegation that long-term use of ankle braces causes weakness in the dynamic ankle stabilizers. However, I have specifically searched the literature for answers to this question, and I have not found any studies specifically looking at this. However, I have found studies exploring the impact of short- and/or long-term ankle bracing on muscle latency, agility, and/or other sports performance elements.

Interestingly, Cordova and Ingersoll found that the amplitude of the peroneus longus stretch reflex is higher after immediate application of lace-up braces when compared to the immediate application of semi-rigid braces and the control. The immediate use of semi-rigid braces did not result in a higher amplitude when compared to the immediate application of lace-up ankle braces. However, after 8 weeks of use, both lace-up and semi-rigid braces demonstrated significant increases in peroneus longus stretch-reflex amplitude when compared to the control.1 This is considered a “good thing” as the peroneus muscles are activated to correct a supination perturbation and maintain functional ankle stability. You can read the authors hypotheses regarding these results on pg. 261.1

Gross and colleagues found that rigid2 and semi-rigid3 braces did not have a negative impact on performance in injured or non-injured subjects during athletic maneuvers. Gross and Liu provide a good summary of evidence regarding the impact of ankle bracing on athletic performance on pg. 575.4 This article was written in 2003, so there might be more current summaries regarding this topic. However, the authors reference multiple studies with conflicting evidence regarding the impact of ankle bracing on athletic performance, specifically 40-meter sprint times, figure-8 run, vertical jump height, broad jump distance, shuttle run performance, and made jump shots (basketball). My opinion: I think the athlete should be educated on the pros and cons of ankle bracing, but from my research and personal experience with prophylactic ankle brace use, the benefits outweigh the cons.

In regards to your excellent question regarding balance training on different surfaces, I did not initially search for any specific answers on the most optimal training surfaces for athletes. Most of the studies I analyzed progressed from a more stable surface to a less stable surface, but that does not answer your question. Eisen et al explored the effects of multiaxial and uniaxial surface balance training in college athletes. The authors did not find any significant differences in star excursion balance test results between different training strategies and the control.5 However, the study had low statistical power. Borreani et al found greatest EMG activity for associated ankle musculature during upright unipedal stance on a soft/compliant (foam) surface with upper extremities engaged using resistance bands. The authors found the least EMG activity of the tibialis anterior and soleus during seated position and the least peroneus longus activity found during erect bipedal position with no resistance band activity. The authors suggest the following progression for increasing the intensity of balance exercises: begin with bilateral exercises while seated on exercise ball (lowest intensity) and progress to unipedal stance on compliant surface (foam) engaging upper extremities with resistance bands to achieve progressively greater muscle activation.6 Currently, I would suggest a similar progression for rehabilitation. Researchers theorize greater afferent input leads to augmented neuromuscular control. I recommend that you implement a variety of balance exercise activities that include unstable and stable surfaces. I hope that helps.

Finally, some of the studies I looked at took into account contact vs. non-contact injuries. Most of the authors of RCTs combined contact and non-contact ankle injuries in their analyses when exploring an intervention, so it is difficult to determine the impact of interventions on contact vs. non-contact injuries. In regards to semi-rigid bracing, Sitler found a significant reduction of ankle injuries in those with a contact mechanism of injury when compared to the control. However, there were no significant differences between the groups when the authors analyzed non-contact MOIs.7 Studies looking at risk factors that predispose one to ankle injury were mostly looking at noncontact MOIs. I am guessing “contact MOIs” would be considered a confounding variable when trying to determine true inherent risk factors. Also, studies looking at incidence of ankle injuries reported greater incidence of contact MOIs vs. non-contact.

If you need more clarification or have any more questions, please feel free to contact me anytime. Thank you, again, for taking such an in-depth look into my capstone work and all your encouragement. Have a good one, Mike.

-Nick

References:

1. Cordova ML, Ingersoll CD. Peroneus longus stretch reflex amplitude increases after ankle brace application. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(3):258–262. doi:10.1136/bjsm.37.3.258.

2. Gross MT, Everts JR, Roberson SE, Roskin DS, Young KD. Effect of Donjoy Ankle Ligament Protector and Aircast Sport-Stirrup orthoses on functional performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;19(3):150–156. doi:10.2519/jospt.1994.19.3.150.

3. Gross MT, Clemence LM, Cox BD, et al. Effect of ankle orthoses on functional performance for individuals with recurrent lateral ankle sprains. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;25(4):245–252. doi:10.2519/jospt.1997.25.4.245.

4. Gross MT, Liu H-Y. The Role of Ankle Bracing for Prevention of Ankle Sprain Injuries. JOSPT. 2003.

5. Eisen TC, Danoff J V, Leone JE, Miller T a. The effects of multiaxial and uniaxial unstable surface balance training in college athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(7):1740–1745. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e2745f.

6. Borreani S, Calatayud J, Martin J, Colado JC, Tella V, Behm D. Exercise intensity progression for exercises performed on unstable and stable platforms based on ankle muscle activation. Gait Posture. 2014;39:404–409. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.08.006.

7. Sitler M, Ryan J, Wheeler B, et al. The Efficacy of a Semirigid Ankle Stabilizer to Reduce Acute Ankle Injuries in Basketball. :454–461.