EFFECTS OF AN 8-WEEK SELF-EFFICACY PLUS EXERCISE INTERVENTION ON PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, QUALITY OF LIFE, AND FATIGUE IN AN INDIVIDUAL WITH PROGRESSIVE MS

By Heather Eustis, SPT

For my capstone I designed and conducted a single-subject study as a research elective during the fall semester. As one of the 2013 recipients of the Multiple Sclerosis Standardized Training and Education Program with University Partners (MS STEP UP) Scholarship, I have spent the last 2 years researching all about MS and discovering areas of interest. One of my main interests was utilizing the construct of self-efficacy to help improve physical activity in persons with advanced MS. As a component of my research, I focused my CAT on this topic. Based off my research, I designed my study to focus on a self-efficacy building intervention on 1 female participant with secondary-progressive MS and severe disability. My study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and consisted of an 8 week self-efficacy plus exercise intervention followed by a 2 month follow up period. After collecting all the data I wrote an abstract for the study which I submitted to the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) annual 2015 conference. My abstract was selected to be a platform presentation. In May 2015 I will present my study during a 15 minute oral presentation at CMSC. Additionally, I have been working on writing the full manuscript for my study which I intend to submit to the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy (JNPT). My advisor Dr. Prue Plummer has been an amazing component in this process helping to guide me during each step of the way. Below is an overview of my study.

Introduction:

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system characterized by an unpredictable and progressive decline in mobility, cognition and other physiologic functions.1,2 Due to the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, individuals with MS are susceptible to noncompliance in health promoting behaviors secondary to many barriers to adherence that span across physical, emotional, social and environmental domains.1–4 Individuals with more advanced MS, such as secondary-progressive MS (SPMS) and primary-progressive MS (PPMS), are particularly susceptible to these barriers as these individuals present with greater functional impairment and subsequent reduced quality of life (QOL) when compared to the most common type of MS, relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).4–7

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms of MS and can play a significant role in a person’s ability to adhere to an exercise program.8 MS-related fatigue combined with decreased mobility often leads to the secondary symptom of depression, which further makes exercise difficult.8 Physical activity has been shown to help manage these symptoms as well as improve functional mobility. Due to the beneficial effects of exercise, it is not surprising that exercise interventions for MS have developed rapidly.7,9–14 Despite the benefits, a large percentage of persons with MS remain inactive, often due to physical (i.e. fatigue) and psychological (i.e. low self-efficacy) barriers that limit sustainability and adherence of an exercise program.12,15–17 Inactivity is particularly prevalent among people with progressive forms of MS, where there is a greater disease burden. Promoting physical activity in this population may require more than just simple instruction and handouts. Therefore, identifying behavioral mediators of physical activity in individuals with MS may help healthcare providers design a sustainable exercise intervention.18,19 Self-efficacy has been recognized as one such mediator, and has been the focus of many behavioral interventions for persons with MS.5,12,16,20–22

Self-efficacy, as proposed by Albert Bandura, is a construct of Social-Cognitive Theory that “specifies a core set of determinants, the mechanism through which they work, and the optimal ways of translating this knowledge into effective health practices”.23 Bandura further defines self-efficacy as someone’s belief to overcome barriers by use of innate abilities.23 High self-efficacy translates into higher goal setting and compliance in reaching that goal with the opposite being true for someone with low self-efficacy.23

Currently, little research has examined self-efficacy in persons with more advanced MS and/or severe disability defined as an Expanded Disability Status Score (EDSS) of ≥7, indicating the individual is primarily restricted to a wheelchair. Most of the research has utilized subjects with RRMS and/or minimal to moderate disability levels (i.e. they are either independently ambulatory or require minimal assistive devices for ambulation such as a single-point cane and/or ankle-foot-orthosis).13,18,24–28 The ability to sustain an exercise program becomes much more challenging among people with more advanced MS and may require additional strategies to promote physical activity, such as self-efficacy interventions. The purpose of this single-subject design was to examine the effects of a self-efficacy plus exercise intervention on physical activity endurance, QOL, fatigue and physical activity level in an individual with SPMS and low self-reported self-efficacy.

The Participant:

The participant for my study was a 60 year old Caucasian female with SPMS and an EDSS score >7. She was diagnosed with MS in 1994 at the age of 40. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed multiple lesions to her cerebellum. At the time of her participation, her most disabling symptoms were fatigue and cerebellar ataxia. She was mainly confined to a wheelchair but would engage in short distance ambulation (5-10 feet) with a rollator and at least moderate assistance by a physical therapy student helper. Usually she would be unable to walk the entire distance of her hallway and would discontinue walking after only a few feet. PT students would regularly come to her home to assist with activities of daily living and help her with her exercises. Despite doing exercises regularly she was very inactive due to the severity of her MS.

The Intervention:

The subject participated in an 8 week self-efficacy plus exercise intervention followed by a 2 month follow up period. The intervention consisted of the following: weekly discussions and MS-related educational presentations; 4 one-on-one sessions with a MS “mentor”; and daily journal logging to record sleep quality, fatigue level, and physical activity. Outcome measures included a modified 5 meter walk test (5MWT), MS Impact Scale (MSIS-29), Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (ESES), Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS), MS Self-Efficacy Scale (MS-SES), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and daily physical activity monitoring. Outcomes were assessed at baseline (wk 0), post-intervention (wk 8), and 2-months post intervention (wk 16). Additionally the participant wore an activity monitor from week 0 to 16 during all waking hours. The participant continued to engage in her regular exercise routine throughout the study period. The topics for the educational presentations were selected by the participant and included the following: assistive devices for spasticity and tremors (i.e., dynamic braces, functional electrical stimulation), online resources for MS, exercise interventions for progressive MS, and stem cell research in MS. The MS “Mentor” was a volunteer with high self-reported self-efficacy who met with the participant 4 times to discuss topics of interest (medical journal of MS, medications, exercise).The educational presentations and mentor sessions focused around the following self-efficacy building components: Identification of challenges related to the topic; strategies to overcome these challenges; what worked & what did not work; and utilization of resources.

The Findings:

There were notable improvements in ESES, MFIS, PHQ-9, sleep quality, and morning fatigue ratings post intervention that were retained at follow up. Gait speed was unchanged. However, the participant was unable to complete the full 5MWT at week 0 and 4 due to increased fatigue, but was able to complete the full measure at week 8 and 16. Activity monitor data revealed the participant increased the amount of steps per day she took from week 0 to 8. This increase was modest but still noteworthy considering her disability level. A final informal interview revealed that the participant found the educational and discussion sessions and mentor sessions the most useful, with the daily journal perceived as least useful. Overall the participant really enjoyed the intervention. Subjective reports included improved walking tolerance and ability to walk the full length of her hallway more often than before the intervention.

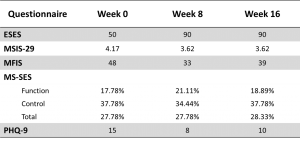

Questionnaires (click on image to enlarge)

Questionnaire scores from week 0 (baseline), to immediately-post intervention (week 8), to 2-month follow-up (week 16) – ESES: Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (range 0 to 100; higher score indicates better self-efficacy to exercise); MSIS-29: Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale -29 (range 1 to 5; higher score indicates greater impact of MS on quality of life); MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (range 0 to 84; higher score indicates greater impact of fatigue on quality of life); MS-SES: Multiple Sclerosis Self-Efficacy Scale (range 10% to 100%; higher score indicates better self-efficacy to overcome MS-related barriers); PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionarie-9 (range 0 to 31; higher score indicates increased depressive symptoms)

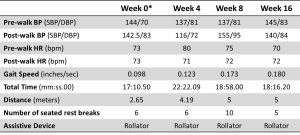

5 Meter Walk Test (click on image to enlarge)

*Split baseline recorded to achieve average baseline score

On week 0 and 4, test was terminated early secondary to subject fatigue and inability to finish required 5 meter distance.

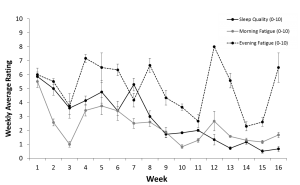

Daily Journal Weekly Averages +/- Standard Error (click on image to enlarge)

Sleep quality (0, fantastic – 10, terrible) and morning and evening fatigue level (0, no fatigue – 10, worst imaginable fatigue) from week 1 to week 16.

Conclusion:

The findings suggest that an 8-week self-efficacy intervention can increase exercise self-efficacy, QOL, and reduce perceived fatigue in a severely disabled individual with progressive MS. Additionally, one-on-one peer mentoring appears to be a very effective method for helping improve self-efficacy. Future research should examine self-efficacy interventions in a randomized controlled trial utilizing a larger sample size of persons with progressive MS and severe disability.

Acknowledgments:

First and foremost I would like to thank Dr. Prue Plummer for being an amazing component of this entire process. With her help I was able to develop this intervention and execute it. She has also been an amazing help during the process of writing the manuscript. I would also like to thank the participant and her husband for their time and willingness to participate in this study. Additionally, I would like to thank Chuck Willingham for volunteering his time to be the MS “mentor” during this study. He was an invaluable component of the intervention and I am very grateful for his involvement. I would also like to thank Lexie Williams and Corinne Bohling for helping with the data collection. I am also grateful for the MS STEP UP Scholarship program for presenting me with these amazing opportunities to explore my interests in MS. I am forever grateful for all those who have made this scholarship possible. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends who supported me throughout this process.

References:

- Schmitt MM, Goverover Y, Deluca J, Chiaravalloti N. Self-efficacy as a predictor of self-reported physical, cognitive, and social functioning in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(1):27-34. doi:10.1037/a0035288.

- Riazi A, Riazi A. Self-effcacy predicts self-reported health status in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004.

- Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM, Gliottoni RC. Physical activity and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: intermediary roles of disability, fatigue, mood, pain, self-efficacy and social support. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14(1):111-124. doi:10.1080/13548500802241902.

- Mitchell AJ, Benito-león J, González JM, Rivera-navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis : integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. 2005;4(September).

- Jongen P, Ruimschotel R. Improved self-efficacy in persons with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis after an intensive social cognitive wellness program with participation of support partners: a 6-months observational study. Heal Qual …. 2014;12(1):40. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-12-40.

- Rovaris M, Confavreux C, Furlan R. Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: current knowledge and future challenges. Lancet …. 2006;5(April):343-354. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442206704100. Accessed November 3, 2014.

- Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16042230.

- Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(September):556-566. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70166-6.

- McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000:85-88. http://journals.lww.com/acsm-essr/Abstract/2000/28020/Self_Efficacy_Determinants_and_Consequences_of.8.aspx. Accessed November 2, 2014.

- Döring A, Pfueller CF, Paul F, Dörr J. Exercise in multiple sclerosis — an integral component of disease management. EPMA J. 2011;3(1):2. doi:10.1007/s13167-011-0136-4.

- Rietberg M, Brooks D, Bmj U, Kwakkel G. Exercise therapy for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2011;(3).

- McAuley E, Motl RW, Morris KS, et al. Enhancing physical activity adherence and well-being in multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2007;13(5):652-659. doi:10.1177/1352458506072188.

- McAuley E, Motl RW, Morris KS, et al. Enhancing physical activity adherence and well-being in multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2007;13(5):652-659.

- Mostert S, Kesselring J. Effects of a short-term exercise training program on aerobic fitness, fatigue, health perception and activity level of subjects with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2002;8(2):161-168. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11990874.

- Motl RW, Dlugonski D, Pilutti L, Sandroff B, McAuley E. Premorbid physical activity predicts disability progression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2012;323(1-2):123-127. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.08.033.

- Motl RW, Snook EM, McAuley E, Scott J a, Douglass ML. Correlates of physical activity among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(2):154-161. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm3202_13.

- Motl RW, McAuley E, Sandroff BM. Longitudinal change in physical activity and its correlates in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1037-1048. doi:10.2522/ptj.20120479.

- Pilutti L a, Dlugonski D, Sandroff BM, Klaren R, Motl RW. Randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention targeting symptoms and physical activity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20(5):594-601. doi:10.1177/1352458513503391.

- Kirkpatrick Pinson DM, Ottens AJ, Fisher T a. Women coping successfully with multiple sclerosis and the precursors of change. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(2):181-193. doi:10.1177/1049732308329465.

- Suh Y, Joshi I, Olsen C, Motl RW. Social Cognitive Predictors of Physical Activity in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Behav Med. 2014. doi:10.1007/s12529-013-9382-2.

- Motl RW, Snook EM. Physical activity, self-efficacy, and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(1):111-115. doi:10.1007/s12160-007-9006-7.

- Motl RW, Dlugonski D, Wójcicki TR, McAuley E, Mohr DC. Internet intervention for increasing physical activity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011;17(1):116-128. doi:10.1177/1352458510383148.

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143-164. doi:10.1177/1090198104263660.

- Bombardier CH, Cunniffe M, Wadhwani R, Gibbons LE, Blake KD, Kraft GH. The Efficacy of Telephone Counseling for Health Promotion in People With Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(10):1849-1856. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2008.03.021.

- Feys P, Tytgat K, Gijbels D, De Groote L, Baert I, Van Asch P. Effects of an 1-day education program on physical functioning, activity and quality of life in community living persons with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;33(3):439-448. doi:10.3233/NRE-130975.

- Motl RW, Dlugonski D, Wójcicki TR, McAuley E, Mohr DC. Internet intervention for increasing physical activity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011;17(1):116-128. doi:10.1177/1352458510383148.

- Plow M, Bethoux F, McDaniel C, McGlynn M, Marcus B. Randomized controlled pilot study of customized pamphlets to promote physical activity and symptom self-management in women with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(2):139-148. doi:10.1177/0269215513494229.

- Thomas S, Thomas PW, Kersten P, et al. A pragmatic parallel arm multi-centre randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a group-based fatigue management programme (FACETS) for people with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(10):1092-1099. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-303816.

3 Responses to “EFFECTS OF AN 8-WEEK SELF-EFFICACY PLUS EXERCISE INTERVENTION ON PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, QUALITY OF LIFE, AND FATIGUE IN AN INDIVIDUAL WITH PROGRESSIVE MS”

Joseph Miller

You would be PERFECT to design such a program. Again, fantastic work

Joe

Heather Eustis

Thank you Joe! I think more research needs to come out in terms of the effectiveness and feasibility of utilizing a self-efficacy intervention in persons with more advanced MS and high disability. However, in the meantime, I think it would be great to see a mentor system developed for persons with MS, like what they do with SCI. It would be good to have a pool of volunteers that PTs could recommend to an appropriate patient. The self-help groups are great, but I think that one-on-one interaction is also very valuable. I also think that PTs could incorporate self-efficacy building techniques in their interventions through patient education. I think we need to be able to recognize who would be appropriate for these additional techniques (ie. during exercise talk about barriers to exercise at home or barriers the pt faced when trying to maintain an exercise program). I think we do this naturally, but by being more aware of the benefits of improving self-efficacy we could be more effective in how to present this information. Based off these discussions we could either provide on-site advice in how to overcome these barriers and also provide appropriate resources (online and/or community). You could even make up your own evidence-based handouts to give to patients that discuss self-efficacy strategies (while making sure to follow up with the patient). What I would LOVE to see in the future is a program actually set up (like Free From Falls) which appropriate participants can attend to learn strategies to improve their levels of self-efficacy. Ideally, this program would also utilize a mentor system. This would be pro bono…and not all therapists may be willing to volunteer his or her time, but I would like to think that most would!

Heather

Joseph Miller

Heather:

Incredible work. I can tell you put a lot hard thought and effect into this project, and I look forward to seeing how it improves patient care. As I was working with your participant last semester, I could tell that she really enjoyed the mentorship and the education. I look forward to your presentation at CMSC and your publication. I do have one additional question. The clinical implications of your study indicate that self-efficacy interventions can be beneficial for individuals with progressive or more severe stages of MS. Given that physical therapists are not directly reimbursed for providing self-efficacy interventions (only), how would you recommend therapists incorporate similar concepts into their practice?

Joe