Background

Prior to this project presenting itself as a possibility, I have always been passionate about evidence based practice in the realms of sports medicine, sports physical therapy, athletic training, and human performance enhancement. Before starting in the DPT program here at UNC, I graduated with my degree in athletic training from Emory & Henry College which allowed me to work in multiple athletic venues across a variety of sports through my clinical affiliations. I have also been very fortunate to work in different roles as a licensed athletic trainer in the state of North Carolina while also studying to become a physical therapist. These experiences have allowed me to form a strong interest in rehabbing athletes with a wide array of impairments and injuries (patellar tendinopathy, lateral ankle sprains, SLAP lesions, patellofemoral pain syndrome), but I am particularly interested in the anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) rehabilitation process. This is a topic I have continued to explore the literature on, discuss with classmates and clinicians, attended continuing education courses for, and even discussed in various journal club meetings.

My partner, Ryan Brooks, and I first heard of this project in October of 2020 from Dr. Louise Thoma who brought the project forward as a potential capstone opportunity. Ryan and I immediately jumped at the chance to participate in the project and to put our brains together to create very useful and ready-to-implement evidence based materials for the practicing clinician. Ryan’s side of the project focused on return to sport testing and in clinic rehab (see Ryan’s project here), while my side of the project involved the on-field rehab process. This portion of the project pushed me to dive into an area I was less familiar with and has helped me grow my base of knowledge exponentially. I feel I have a strong foundational knowledge in the areas of resistance training in rehab, current best practices for testing in the rehab process, and in exercise prescription, but the on-field rehab area was one that I had not previously taken a deep dive into.

Statement of Need

Despite some common views of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) rehabilitation within the profession, there is a clear and significant gap faced by athletes who incur this injury and attempt to return to high-level sporting activities. While outcomes vary and the exact number of secondary ACL rupture following ACLR is not known, it has been reported that reinjury occurs in 6% to 31% of cases where injuries can be seen to either the postoperative or contralateral knee.1,2 There are many proposed theories and correlations related to why retear rates and/or contralateral knee injuries may be this high ranging from poor testing procedures in the rehab process, lack of recovery of force production qualities in the quadriceps muscle group, altered knee kinematics in functional or sport-specific tasks, lack of use of criterion-based rehab protocols, and athletes returning to sport too soon after injury. Within this process and timeline falls a difficult portion of rehab, that can greatly aid athletes in a successful return to sport program, known as on-field rehabilitation.

On-field rehab refers to the “period between gym based rehab and competitive team environment” and currently represents an area with a paucity of evidence in how to properly conduct it.3 This period of time represents a crucial point for rehabilitation professionals working with athletes post ACLR as injuries to the graft have been noted to occur early into the return to play (competitive) period (injuries can occur shortly after return to full match play and within the first few months of return to competition).4,5 These numbers represent the period after rehabilitation has been completed and mark the importance of using a proper transitional period from gym based rehab to full speed competition. The current lack of evidence in how the rehab professional should approach the on-field rehabilitation period presents a clear issue, but this capstone project seeks to explore the literature that does exist and create a guide for clinicians that is practical and can be readily implemented in the outpatient setting to ensure the athlete has been exposed to the movements, speeds, durations, energy systems demands, and sport-specific skills needed to succeed in their respective sport. In real world clinics (such as the typical outpatient orthopedic setting), there are certain constraints which this capstone will seek to discuss and address such as clinic space, equipment, rehab duration, and increasing knowledge of performance enhancement and reinjury risk reduction throughout the process. While covering the specifics of many different sports would be outside the scope of this capstone, what will be provided to the clinician is a set of guidelines with specific goals that need to be achieved during the phases of on-field rehab to guide the clinician with their decision making based on the athlete they are working with.

Purpose

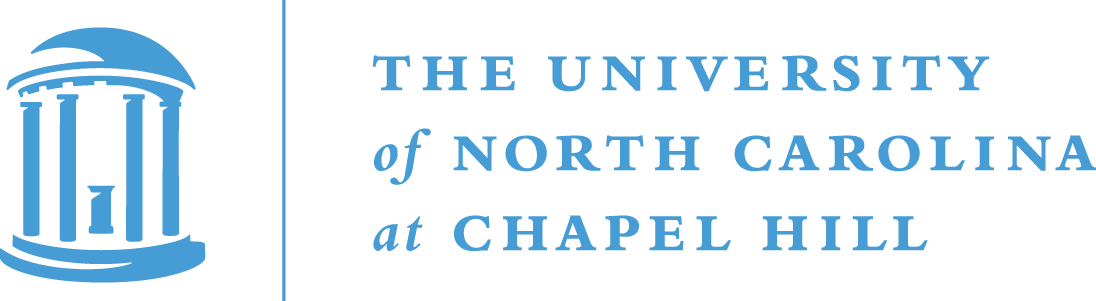

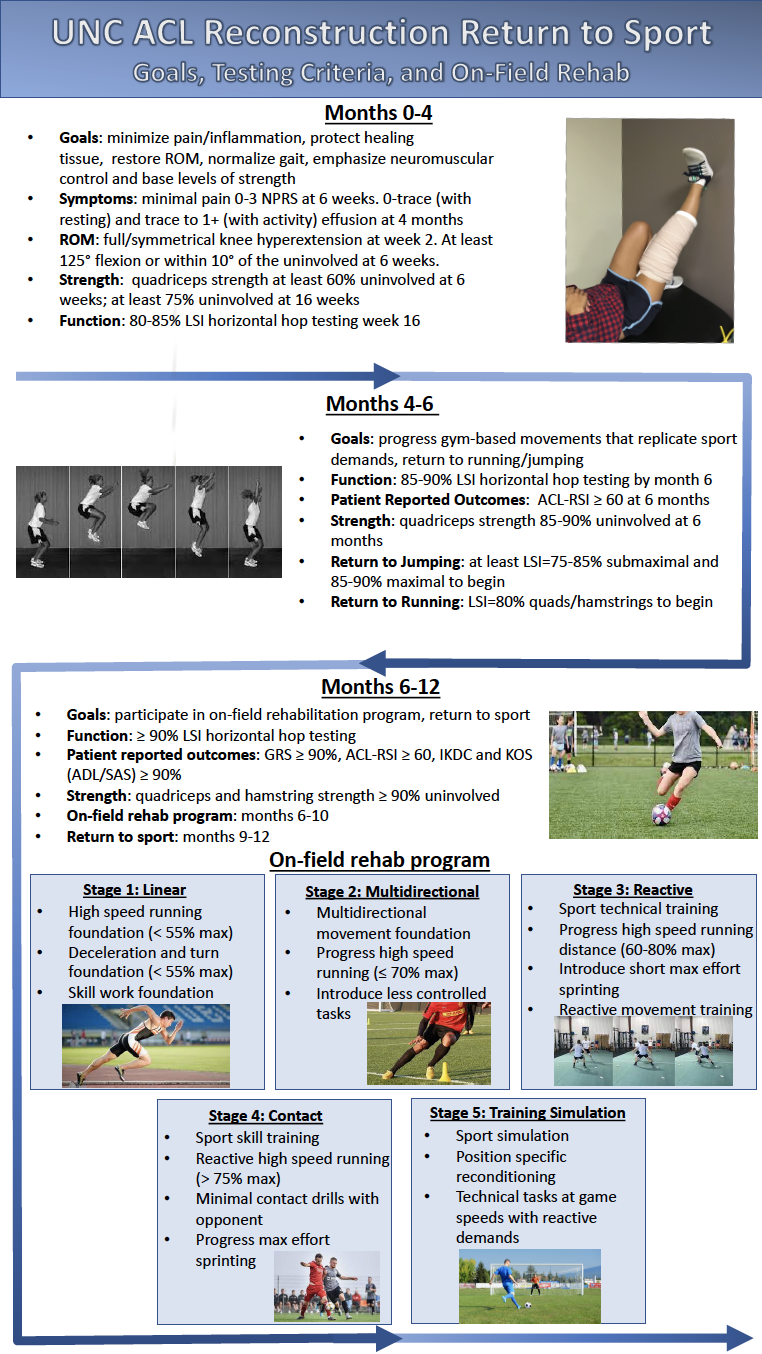

The overall goal of our project was to create a set of materials focusing on ACLR testing criteria and on-field rehab that could be readily implemented by the practicing clinician. For more information on the criteria based testing see Ryan’s side of the project here. The goal for the on-field rehab portion evolved as we continued having discussions amongst the project members and the committee, eventually forming into the goal of creating one page summary sheets involving the stages of on-field rehab, entry criteria for each stage, goals of the stages, and example activities as well. Additionally, we created a database of videos which are around one minute each in length and give a snapshot of drills, tasks, and exercises that can be immediately used by clinicians. We also set out with the goal to create a one page summary for patients that parallels that of the clinician, with simpler language, so that they can be on the same page with each step of the process. To address health literacy and create engaging educational materials, we also wanted to create infographics for both the clinician and the patient. Through these materials, we were able to explain and expand upon the transitional period known as on-field rehab as it is a nuanced topic with emerging information related to its importance in the return to sport process.

Products

Products created include the following:

- One page summary handouts (clinician, patient, simple deceleration progression)

- Capstone Google Form outline for clinicians

- Narrative review for clinicians

- Short health literacy explanation

- Video presentation for clinicians

- Presentation slide deck

- Clinician infographic

- Patient infographic

Evaluation

Evaluation was, is, and continues to be a fluid process with multiple sources of information. One of the first evaluation methods used were frequent meetings with my partner Ryan Brooks (weekly and up to three times per week) to discuss both sides of the project. Ryan is a great source of information, especially with his background in strength and conditioning, and these meetings allowed us opportunities to bounce ideas back and forth and brainstorm our topics. During these meetings, we also created the infographics for our project which allowed us a base of information to begin asynchronous work before coming together a final time to touch up the infographics. Along with these meetings, we had periodic meetings with our committee to discuss the status of materials, changes to our plans, new ideas, and to receive feedback on the direction in which the project was heading. At the midterm, we submitted materials for feedback from the committee and began to create and/or refine the products which are presented on this website. This allowed us to identify gaps in the presentation of the materials and to create concise products. Finally, our materials were shared with physical therapists within the UNC outpatient setting and physicians associated with ACLR patients at UNC along with a Google Form questionnaire for feedback (as of April 7th). We consider these individuals “stakeholders” in the project and are currently in the process of receiving and compiling responses related to the materials in order to see what changes may or may not be necessary to ensure the usability of the materials. Once enough responses have been recorded, specific changes can be made which will then make the final resources appropriate for implementation.

Self-assessment

As I stated previously, this project gave me a greater understanding of the world of on-field rehab following ACLR related to possible stages to use, progressions to follow, theoretical concepts to implement, and the current body of evidence on the topic. My ultimate goal is to work in the sports medicine/rehab setting with athletes participating in sports with high risk demands and activities that may lead to athletes incurring ACL injuries. This project has allowed me to boost my confidence in the transitional period between traditional gym-based rehab and returning athletes to competition and I feel will serve me well in the future. I look forward to compiling the data we receive from the feedback forms to make some final edits to the materials and ultimately to see them used in practice in the outpatient setting here at UNC. I also look forward to (potentially) presenting these materials as part of an inservice style presentation during my final rotation in outpatient orthopedics here at UNC.

Acknowledgement

First, I cannot thank all of the following individuals enough for their support throughout the process. It has truly been a pleasure working with you all.

To Ryan Brooks, thank you for taking on yet another project with me and for always being a great partner. We have teamed up since the very first day of PT school and I am proud that this is the project that we get to go out on. We have always kept each other motivated in staying up to date with sports medicine literature and practices. I always look forward to our conversations related to the profession and to hearing your insights when I have questions. You have been a wealth of knowledge for me, a great lab partner, a great project partner, and most importantly a great friend. You have an incredibly bright career ahead of you and I am excited to follow it.

To Dr. Louise Thoma, thank you for being our capstone advisor and for bringing this project to our attention. Ryan and I were planning to work on a project together regardless of the topic chosen and the fact that we had the opportunity to work on a project such as this was incredible. We both learned so much in talking to you, both related to the project and for moving our careers forward in the coming years. Your feedback was always helpful in moving the project forward and keeping us on track with our goals. Thank you for everything and I look forward to staying in touch in the future!

To Dr. Madison Franek and Dr. Michael Lewek, thank you both for being our committee members and for allowing us to reach out with questions and for guidance through this process. Our email and Zoom discussions aided so much in creating the foundation for the project as well as to keep the project in a concise and realistically usable fashion. Madison, your expertise in the areas of strength and conditioning and on-field rehab helped me to find resources and understand how to translate them to practice in an effective manner. I always enjoyed reading the additional articles you were able to share to advance the project along.

References for this page (see resources for other reference materials).

- Wright RW, Magnussen RA, Dunn WR, Spindler KP. Ipsilateral Graft and Contralateral ACL Rupture at Five Years or More Following ACL Reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(12):1159-1165. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.00898

- Paterno MV. Incidence and Predictors of Second Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury After Primary Reconstruction and Return to Sport. J Athl Train. 2015;50(10):1097-1099. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-50.10.07

- Buckthorpe M, Della Villa F, Della Villa S, Roi GS. On-field Rehabilitation Part 1: 4 Pillars of High-Quality On-field Rehabilitation Are Restoring Movement Quality, Physical Conditioning, Restoring Sport-Specific Skills, and Progressively Developing Chronic Training Load. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):565-569. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8954

- Buckthorpe M, Della Villa F, Della Villa S, Roi GS. On-field Rehabilitation Part 2: A 5-Stage Program for the Soccer Player Focused on Linear Movements, Multidirectional Movements, Soccer-Specific Skills, Soccer-Specific Movements, and Modified Practice. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):570-575. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8952

- Waldén M, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, Ekstrand J. ACL injuries in men’s professional football: a 15-year prospective study on time trends and return-to-play rates reveals only 65% of players still play at the top level 3 years after ACL rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(12):744-750. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095952

8 Responses to “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Return To Sport: On-field Rehab”

Louise Thoma

Congratulations on creating clinically useful products to help guide a phase of rehabilitation that is hard to pin down! On-field rehabilitation has many considerations and you have done a wonderful job synthesizing the limited available literature and creating a structure that will help clinicians execute on-field rehab in practice! I look forward to seeing how this gets implemented in the UNC clinics, and how you use this Capstone experience to inform how you develop future tools and products as you enter the clinic!!

Debbie Thorpe

Brandon

Really nice work! You created numerous valuable resources for clinicians and patients. It is evident that you delved deeply into the literature and did a nice job of synthesizing the evidence. I really like your info-graphics..easy to understand and complete. I enjoyed your voice thread as well, if faculty would like to get your permission to use it as content in the curriculum, the voice thread would be a good way to have the students view the presentation asynchronously. The videos in the presentation really helped with understanding.

Fantastic work!!

Good luck with the rest of your clinical rotations!

Best

Debbie

az3ft

Awesome project and content, Brandon! I know this project was a massive undertaking for you and Ryan, but I think the product you all have produced is exceptional (especially given our time constraints). The clinician presentation is a wonderful summary of the narrative review. The video and graphic components really help to illustrate the points you are trying to make when it came to the estimation of percentage maxes with running and deceleration. I especially appreciate your commentary about how the current practice for most clinics is almost all based on gym movements and facility induced, environmental constraints. Although the patient does need a”big engine” as you mentioned, it is not the entire picture. Getting trainers and especially coaches to follow these guidelines is especially important once the patient leaves our clinic and is beginning to progress practice participation. The coaching staff outreach and parent education portion of this will be something I try to emphasize with this information you all have synthesized for us. I do have a question for you when it comes to the introduction of ball skills with the various levels of progression. At what point do you think it is safest to introduce the use of a ball or implement? Thinking through this with soccer, the pursuit of a ball could come as early as the multi-directional phase. However, for a sport like football, a WR’s ability to change direction while running routes in practice is zero contact but likely at near competition speed. The same is likely for competitive dancers or performing artists. I understand this is a very nuanced discussion that may come into play with your information on change of direction, but I would love to hear your thoughts and ideas on the topic.

Brandon Surber

Hey Alan,

Thanks for the wonderful comments and for producing a thought provoking question! It can be really challenging to pinpoint exactly where a drill or practice movement can fall along this spectrum due to the multivariable nature across sports (speeds, types of cutting, nature of defense/offense). This is something I thought a lot about while working on this project and originally wanted to address across many sports, but the project seemed like too large of a scope which led us to focus on some example videos for soccer and basketball due to injury data related to those sports. Given the nuanced nature you mentioned, it is hard to say what is “right or wrong” and I believe if we follow the progression from simple, closed, and preplanned tasks to more complex, open, and reactive tasks, it would place the athlete in a good spot to progress while minimizing the chances of reinjury (so long as logical progressions in workload are followed). Introducing a ball can come as early as the linear stage with very simple tasks such as back and forth toe taps in soccer or dribbling in place with a basketball. With the wide receiver example in football, we could see stationary passing introduced in the multidirectional phase. Keeping with that example we could think of a simple progression as being standard deceleration drills from stage one progressing to slow and shallow angle route running, then progressing to slightly faster shallow angle route running with preplanned passes, then increased speeds with sharper angle cuts and passing, then reactive route running based on a defender’s positioning, and then full speed route running with contact from a defender while catching the ball. That is a very (very) general example and would have many iterations and specifics within the phases, but I hope it helps some!

Ana-Clara Caldwell

Brandon,

It brings me joy to see you work on a project that you are so passionate and knowledgeable about! I enjoyed reading through your materials. During my first rotation, I did an in-service on return to sport after common sports injuries, including ACL injuries! There is so much research about ACL injuries that it can be daunting! I know this project was a big task for you and Ryan, but I can say the products will be well utilized and very much appreciated! ACL injuries are so common, and I know that these resources will be used in the clinic by many as they are both easy to understand and comprehensive. I appreciate that you all focused on the return to sport and on-field rehab as I believe this is an area that many clinicians are not as familiar with. These resources will help provide the knowledge necessary to carry a patient all the way through rehab and back to high-level sport. I know I will be referring to these in the future! Thanks for all of your hard work and congratulations!

Brandon Surber

Hey AC!

Thank you for the very kind comments and I am glad you found the materials helpful! I had a blast working on this project and especially in working with Ryan on something so detailed. He is brilliant with this stuff and he put in a ton of work digging through the evidence for the battery of testing that came out of the project. I am looking forward to the feedback this gets from being in clinical practice and hope it continues to help everyone as we look to improve our athletes’ return to sport processes.

mcgh

Brandon, congrats to you and Ryan on finishing capstone – this project is very well done, I’m really impressed and I am excited to implement the products you all produced into my own practice! I really appreciate that you created both clinician and patient handouts, especially for young athletes looking to return to sport I can imagine that any and all information we are able to provide to them as clinicians can help to ease their potential fears surrounding surgery, rehab, and the potential for re-injury as you mentioned. Rehab after ACL reconstruction is not an area that I have personally had a lot of experience in during my clinicians thus far, so this is an awesome resource, between both you and Ryans products, to help guide an athlete through the rehabilitation process from within the clinic to getting back out onto the field. As you mentioned, therapists working within the outpatient orthopedics setting, not just within a sports ortho clinic, are likely to see athletes recovering from ACL reconstruction on a regular basis and we need to be just as prepared to treat these dynamic, high-level athletes as we are to treat a patient with a post-operative joint replacement. I have always appreciated your passion for evidence-based practice in moving our profession forward and I think this is an excellent resource to facilitate that. Thank you to both you and Ryan for your hard work in creating these awesome resources, I know I will definitely be returning to these when treating athletes recovering from ACL injuries!

Brandon Surber

Hey Heather!

Thank you for the kind comments on the project and I am glad you liked the materials. I was really excited to help create something that puts the patient and clinician on the same wavelength while giving the patient a simplified, but still in depth, understanding of the rehab process. We really wanted to reach individuals in the outpatient orthopedic setting as you stated as this is where many young competitive and recreational athletes receive their care. Due to clinical constraints and not having a specialized focus in athletics, it can potentially be difficult to provide these patients with the best quality of care possible, but we hope these resources play a small part in improving these scenarios!