Background

I am a “big picture” thinker, and I have always enjoyed analyzing how the various parts of something connect and influence one another. As I have moved through the DPT curriculum, I have become increasingly fascinated with looking at the contributions and influences of the various physical, psychological, social, and environmental factors on one another, and on physical therapy outcomes for individual patients.

One of my primary clinical interests relates to health promotion within routine practice, and the practice model I align with most closely is one which emphasizes wellness, rather than illness; however, I found that although I understood the theories and models discussed in classes, what this type of approach looked like in routine PT clinical practice remained a bit of an enigma to me. Upon further discussion, many of my peers expressed similar feelings about this topic. With current evidence supporting more biopsychosocial approaches to care, I found it curious how many PTs still seem to support the narratives of a pathoanatomical and biomedical models through their approaches to patient care.

I kept searching the literature for a guide that outlined actionable steps and strategies a PT could utilize the next day in the clinic with their patients so that I could better understand what this type of approach to care looked like in practice; however, I was never able to find what I was looking for. To combat this issue, I decided to try to make my own guide, and a guide for other students and clinicians who shared my interests. I want to help facilitate a practice change in the physical therapy profession, and chose to do so through a psychologically informed approach to health behavior change.

Statement of Need

The “whole person” is more than the sum of their ‘parts’ or ‘impairments’, yet individuals are still being treated by clinicians as less than whole. We live in a society which values ‘quick fixes’ and symptom masking over lifestyle-related behavior changes and self-management. To quote the documentary, Escape Fire,1 we have become more of a ‘disease care’ system than a ‘health care’ system. Most current clinical practice guidelines recommend a biopsychosocial perspective when treating patients with musculoskeletal conditions through consideration of the various physical, psychological, social, and lifestyle factors a patient may experience. Although there has been a general shift towards more biopsychosocial and patient-centered approaches, research supports that current training interventions are insufficient for PTs to be comfortable with delivering these types of interventions.2 To best serve our patients and communities, we must be able to consider the many factors which may influence wellbeing and move beyond strictly biomedical or pathoanatomical explanations.

According to research from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC),3 6 in 10 adults in the US suffer from a chronic disease and 4 in 10 have been diagnosed with 2 or more. Chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the U.S., and the leading drivers of the nation’s $3.5 trillion in annual health care costs. Healthy behavior changes are the primary and most effective interventions for addressing disease burden and improving wellness for those suffering from them. Physical activity is well-supported by unequivocal evidence of its positive effects, and appears to be the most important and effective intervention PTs can incorporate into every patient/client plan of care to promote health and wellness.4 Unfortunately, in a recent sample of outpatient PTs, only 12% reported that they regularly promote physical activity in their practice.5

There is a need for more extensive clinical training in biopsychosocial approaches to care, and a need for improved physical activity health promotion in routine physical therapy practice.

Below I have provided the conclusion from my synthesis of the research on psychologically informed physical therapy practice:

“Psychologically-informed practice, specifically, the integration of cognitive and behavioral focused strategies, as a method of delivery or as adjunct to routine physical therapy care, delivered by physical therapists, is effective at improving psychosocial and clinical outcomes related to pain interference, disability, and general mental and physical health, improving self-efficacy and reducing dysfunctional fear avoidance beliefs with moderate to large effect sizes.”

Purpose

The primary purpose of this project was to create an evidence based, psychologically-informed guide that physical therapists could utilize to better promote physical activity and exercise in their routine clinical practice. This guide takes the form of a clinician manual with a full reference guide, and has been adapted into a PowerPoint presentation which is available to be presented as an in-service or as a Voice Thread. These resources aim to help facilitate a change in PT practice to one which better recognizes the multifaceted and interrelated nature of the various biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors which are well supported by current practice guidelines for their influence on patient outcomes and overall wellbeing. I chose to focus on physical activity health promotion, specifically, because of its well-understood benefits on health and wellbeing and its obvious overlap with physical therapy as a profession.

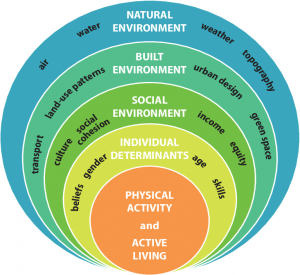

Figure 1: Social Ecological Model of Physical Activity Promotion6

Products

This project encompasses a very large body of information and research. The evidence table provides the research which helped guide the production of the manuals. I also interviewed various clinicians, including two longer interviews with Morven Malay, PT, DPT and Zachary Stearns, PT, DPT, in order to help supplement the evidence and bridge the gap between the research / theory and clinical practice.

Based on the literature, I created a full reference guide with background, theories, models, and extensive information regarding a psychologically informed approach to health behavior change. With feedback from my committee members, and to make this information more accessible to clinicians, I then adapted a shorter clinician manual which outlines various actionable strategies in the form of a S.O.A.P. note. This formatting style was an attempt to help clinicians visualize where in the evaluation or treatment session the specific skills might take place. The information from the shortened clinician manual is also adapted into a PowerPoint format so that it can be presented to other clinicians in the form of an in-service or Voice Thread.

Health Literacy

Although my target audiences are physical therapists and DPT students, I recognize that many of this information may be new or unfamiliar. In recognition of this, and based upon the research, I have provided various materials including a shorter clinician manual with charts and tables, a full reference guide for background information, a PowerPoint presentation, and various activities and summary sections embedded within these products. Further, I have emphasized health literacy within the products themselves, as personal health literacy is one of the primary determinants of one’s self-efficacy with self-management. Within all of the products, I have provided an emphasis on repetition and exposure, as these are crucial for both learning and behavior change.

Below I have listed my products:

-

- Final Evidence Table & Synthesis

- This product is supplemented by my: Critically Appraised Topic (CAT)

- The conclusion of this CAT is provided in the quote above.

- Appendix

- This product is supplemented by my: Critically Appraised Topic (CAT)

- Clinician Manual: Full Reference Guide

- Clinician Manual & Workbook

- Clinician PowerPoint Manual

- Final Evidence Table & Synthesis

Evaluation

The evaluation component of this project is based off of the following learning objectives:

After reviewing these materials, learners will be able to:

- Describe what psychologically informed PT practice is and how it can improve the quality & deliverance of physical activity health promotion.

- Describe strategies that can be utilized to better tailor PA-promoting interventions based on screening results.

- List barriers to increasing physical activity levels and describe potential ways to overcome these barriers.

- Perform a self-reflection on current practices and name 1 or more strategies they are able and willing to implement in their own practice to better promote physical activity in their patients.

- Identify resources for learning more about psychologically informed strategies and physical activity promoting approaches.

This evaluation component is also developed to help obtain feedback from those who work through the manual or attend the presentation so that improvements can be made. This can be viewed here: Evaluation Component

Self Reflection

This project was very large and it was difficult to try to organize the information in a way that was succinct enough to be easily utilized by clinicians. Summarizing this information too much does not do it justice. I originally wanted to make a manual that encompassed the 5 commonly cited domains of health promotion (physical activity, stress management, sleep hygiene, eating habits, & substance use), but quickly realized that this was well beyond the scope of a capstone project, and would need to take the form of a full continuing education course (or series of courses), rather than a brief manual. I have a much better understanding of how extensive a research project can be, and how involved each individual topic of health promotion is. The following quote from my CAT summarizes this point:

“These strategies should not be passively integrated. Effective implementation requires extensive learning, with the most effective programs often totaling ~100-250 hours of didactic, experiential, and supervised training.”

However, the following key point from my clinician manual is equally worth noting:

“Even incremental changes and progress have the potential to result in significant improvements and change long term.”

I am thankful to have been given the opportunity to do this project and to create something that may contribute to the profession at large. Even if the (relatively) few people who read this can take even 1 of these strategies with them into the clinic to use with their patients, I will be thankful to have been able to help them do so.

Acknowledgements

My committee members and peers were central to my ability to create this manual, and I am so thankful to have collaborated with them all.

- Michael McMorris, PT, DPT

- “McMike”- Thank you for agreeing to be my advisor, for coordinating feedback, and for all of the e-mails and Zoom meetings throughout the past months (and years!). Thank you for helping me stay organized and trying to keep me from getting in too far over my head. Further, thank you for brainstorming with me, for all the words of encouragement, and for demonstrating to me that you really cared that we accomplished what we set out to.

- Jennifer Cooke, PT, DPT

- Jennifer- Thank you for helping me with the research and helping guide my interests and learning in the realm of health promotion & wellness. Additionally, thank you for meeting with me and for joining the quest to try to keep me from getting in too far over my head.

- Morven Malay, PT, DPT

- Morven- Thank you for agreeing to be a part of my committee even before we had “met” (virtually). Further, thank you providing your clinical expertise and for maintaining such an active role in this project! Your clinical tips and the information you provided during the interview were central to my ability to tie everything together into the clinician manual.

Additionally, I would like to recognize the following people for their help & contributions to this project:

- Zachary Stearns, PT, DPT

- Conor McClure, PT, DPT

- My Classmates (c/o 2021)

Bibliography

- Heineman M. Escape Fire: the fight to rescue American healthcare. Santa Monica, CA: Lionsgate; 2013.

- Holopainen R, Simpson P, Piirainen A, et al. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Pain. 2020;161(6):1150-1168. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001809

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). Chronic Diseases in America | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm. Published December 1, 2021. Accessed January 5, 2021.

- Bezner JR. Promoting health and wellness: implications for physical therapist practice. Phys Ther. 2015;95(10):1433-1444. doi:10.2522/ptj.20140271

- Rethorn ZD, Covington JK, Cook CE, Bezner JR. Physical activity promotion attitudes and practices among outpatient physical therapists: results of a national survey. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 44(1):25-34. doi:10.1519/JPT.0000000000000289

- Bornstein D, Davis W. The Transportation Profession’s Role in Improving Public Health. Institute of Transportation Engineers Journal. 2014;84:19-24.

10 Responses to “A Psychologically Informed Guide to Physical Activity Health Promotion in Routine PT Practice”

Debbie Thorpe

Hi Kelsi

What an “all encompassing” project! You did a good job of presenting the philosophy of PT practice treating the “whole person”. I think you can take this project in many directions in the future and as you get more clinical experience as a licensed therapist, you can refine from a different lens. Great work! Good luck with the rest of your clinical rotations!

Best

Debbie

kelsikaz

Hi Debbie,

Thank you so much! And thank you for all the feedback and for coordinating the capstone project and course for us. I am excited to see where I can take this project in the future.

Best,

Kelsi

McMike

Kelsi,

I am proud to have been part of your team through this project. You have done an impressive job wrestling through the mounds of evidence producing very practical end products. Thank you for hanging in there to the end for the betterment of the profession, great job!!

kelsikaz

McMike,

Thank you for all the support and collaboration, for the many e-mails and zoom calls, for the feedback, and for helping me reach the goals I set for this project. I appreciate you so much!

Best,

Kelsi

Jennifer Cooke

Excellent work Kelsi! You have thoroughly researched and designed a tremendous topic that is very necessary for the profession. I cannot wait to see where you take this! Congratulations!

kelsikaz

Jennifer,

Thank you so much for being a part of this project! I am grateful for your guidance and feedback. Also, thank you for helping guide some of my earlier learning in your H&W class!

Best,

Kelsi

Rachael Fiorentino

Kelsi,

I can’t even begin to imagine the amount of hours it must have taken to collect and synthesize this vast amount of information into the products that you have presented on this website, especially knowing your love of internet rabbit holes. I am so impressed by your clinical manual and can not wait to fully digest it (there is a lot of information there), learn from it and use your guide in my own future practices. Additionally, the idea of ‘psychologically informed PT practice’ was brought up by a PT in Oregon I was interviewing and she was saying a) how it was something she wished she learned more about in PT school and b) that she wished there were more resources out there regarding it. I can’t wait to share this with her as well, as I am sure she would love to read through your materials. I am proud to have sat next to you (and all your drinks) for the past 2 years and I have no doubt you will be doing great things in the next steps in your PT journey.

kelsikaz

Rachael,

Thank you so much for these words! Many hours (and hours, and hours, and…) were involved in my attempt to synthesize the vast amount of information and evidence encompassed within this topic. Many internet rabbit holes were pursued and many more were grudgingly ignored to try to maintain some semblance of feasibility (and sanity).

I am so happy that you are sharing with your friend in Oregon! I hope this can help her and her practice in some way.

I (and all my coffees, waters, and teas) have enjoyed sitting next to you the past few years as well, and I feel the same when I think of you and your own PT journey. I can’t wait to read through and learn from your project, as well!

Best,

Kelsi

jchurst

Kelsi, I’m actually in awe of the scope of your project. This is an ambitious topic, and one we have talked around frequently as you mention. I deeply respect the countless hours that went into compiling all of those complex discussions in class about integrating the multiple facets of wellness into a cohesive whole. What you have done feels like the compilation of hundreds of small conversations, from various classes, and pulled them all together here. What’s more, you’ve taken a lot of the dryer material (motivational interviewing for example), and put it in an important context.

I further appreciate that you discuss barriers and solutions not just on the patient level, or PT level, but also on the clinical level. As someone working with 2, sometimes 3 patients in an hour, I often have to maximize the efficiency of my time with activity, and it may seem like a ‘waste’ to an Admin that I might choose to spend some of that precious time on education, or planning out behavioral changes. The very infrastructure of the medical system is not built for the kind of whole scope, integrated approach you advocate, but is not entirely unsuited to it. I appreciate the solutions, including specific billing recommendations.

What’s really beautiful to me, is that I feel this is my practice. This is how I approach healthcare, and I can often feel under-resourced exactly like you mention, because there is no comprehensive guide. I have pieced together my own movement theories from more alternative practices outside of school (Visceral manipulation, modern dance, power lifting, pelvic floor therapy), and so to see someone else not only facing these same choices, but having the gumption to go out and MAKE a guide when they couldn’t find one is inspiring. I’m so happy to see some of my own thoughts echoed, and to now have a resource to further expand my PIPT practice!

Well done, my friend. What you have done is inspiring.

kelsikaz

JJ,

Thank you for this response! We have discussed much of these topics throughout the past 3 years, and I am happy to have been given the opportunity to compile this all into a comprehensive guide. I am really thankful that you appreciated the difficulty I faced trying to succinctly summarize such a large breadth of material, and to make concrete the many theories, models, and approaches that we have discussed.

The stark contrast between the ideology that underlies this project and the reality of our health care system has been quite notable since being back in the clinic, and I think you hit the proverbial nail on the head by discussing your current clinic situation of 2-3 patients per hour. Our system is simply not set up in a way which allows this type of practice, at least to its full extent. I tried to choose the types of strategies and approaches that fell most in line with routine PT practice, through an emphasis on communication differences and tweaks to things like goal setting in order to show people that this type of difference is possible. My main takeaway from the whole project comes down to “incremental progress”: even small changes can cause significant improvements. If even one person adopts one of these techniques into their practice, it can make a big difference long-term.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful comment!

-Kelsi