Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction,

Rehabilitation, and Return-to-Play

In August 2013 it will be the 9-year anniversary of the day I tore my anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and medial collateral ligament playing football. At the time it was a devastating event and being a teenage boy I thought my life was over. As it turns out that day did change my life forever, but in the best way possible. Until that point I had dreamt of becoming an architect but once I experience physical therapy first-hand I knew what I was meant to do. My injury drove me into the field of physical therapy because of the wonderful care I received while rehabilitating. From that point on I wanted to help others to get back to what they loved most.

My efforts for the last year have been tied to indulging in the literature as it relates to ACL injuries. In Evidence Based Practice II, I developed the following PICO question: For athletes, who underwent ACL reconstruction, is an accelerated rehabilitation protocol or nonaccelerated protocol associated with improved function and a quicker return to play? After canvasing the literature I developed an evidence table to summarize my findings. What I really pulled away from the evidence was our favorite answer “It depends.” Most of the evidence available is weak and authors disagree on optimal exercises and time frames. The valuable information that I managed to gain from the literature review is as follows:

- Early ROM and WBAT have been associated with more rapid gain of ROM without increasing the laxity of the ligament (Beynnon et al, 2011; DeCarlo et al, 1992)

- Locking a patient’s brace in extension following surgery allows for extension ROM to be preserved or reacquired faster (Melegati et al, 2003).

- Inclusion of sport specific drills, as early as 6 weeks post-surgery, appears to allow for an earlier return to play and improved outcomes (Wright et al, 2008; Beynnon et al, 2011; DeCarlo et al, 1992; Roi et al, 2005). (Exercises should be added in slowly and progressed based on patient tolerance and healing of the tissue).

- Criterion-based progression can provide clinicians with objective reasoning for progression to the next stage of rehabilitation. Criterion-based progression allows for a more individualized treatment plan based on the patient’s stage of recovery, response to exercise, and goals for rehabilitation (Roi et al, 2005).

In addition to my evidence table I also wrote a research paper on the ACL that includes a review of anatomy, mechanism of injury, incidence rates, risk factors, special tests, injury prevention, conservative treatment, surgery, summary of accelerated versus nonaccelerated protocols, and outcome measures. From the development of this paper I was able to gain an understanding of the overall principles necessary for treatment of this population.

At the beginning of the spring semester I was confident that my capstone would develop into a module that incorporated my paper and evidence table into a finished project. However, my mind was focused on developing the “gold standard” protocol for ACL rehabilitation. After meeting with a colleague I was enlightened that a standard protocol for ACL rehabilitation wasn’t necessary, as we have been taught to be critical thinkers about what our patients need. This statement along with my attendance to a Combined Sections course on return-to-play, got my wheels turning in a new direction.

I collaborated with Angela Lauten to develop a Voicethread module on ACL reconstruction (ACLR), which discusses tissue properties, risk factors, biomechanics, graft types, surgery techniques, rehabilitation progression, outcome measures, and return-to-play criteria. The Voicethread was prepared for inclusion in the Musculoskeletal II course as a supplemental resource to Jon Hacke’s knee presentation. Angela took the reigns for the first half of topics listed above, while I focused on applying the principles to rehabilitation and return-to-play. I went back to the literature to find more support for criterion-based progression and return-to-play criteria. You can access my resources at the end of the Voicethread, but I also tried to reference all my points directly on the slides (PDF version) I created.

From my additional literature review I was able to understand that it is critical to constantly assess the patient’s status, especially prior to advancing the patient to the next phase of rehabilitation. Myer et al produced a clinical commentary article that discusses two main phases of rehabilitation: Early and Late phases (Myer et al, 2006). From this article we can understand that the Early phase is controlled by ROM, pain, swelling, and gait. It is a period of time where progression is restricted and controlled. The Late phase is more variable and the evidence lacks on when and how much sport specific training should be performed. Due to the lack of standardization it is suggested that we standardize progression based on objective measures. The most widely suggested progression criteria include pain, swelling, ROM, strength measurements (isokinetic preferred), and functional measures.

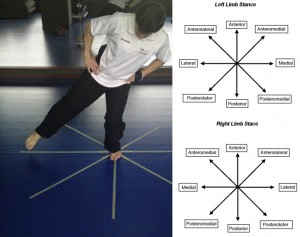

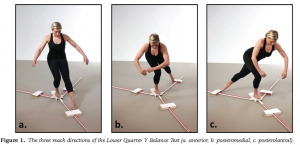

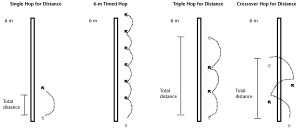

Another area of focus for this project was outcome measures that are appropriate for measuring stability of the patient prior to initiation of sport specific drills and return-to-play. From the literature and clinician recommendation the Star Excursion Balance Test, the Y-Balance Test, and Hop Tests appear to be the most appropriate measures for patients following ACLR. I developed a handout for clinicians and students that describes these measures including measurement norms and psychometric properties. My hope with the handout is that it is a simple clinical reference and that it will encourage the use of reliable and valid outcome measures in this patient population.

Angela and I developed an evaluation form for our committee members to assess our presentation prior to publishing it for our fellow UNC PT students. Feedback was incorporated into the presentation and handout from each committee member.

I would like to give special thanks to those who participated in the development of this project:

Angela Lauten (Partner), Mike McMorris (evidence table critique), Mike Gross (Advisor, ACL paper critique), Jon Hacke (committee member), and James Massey (committee member).

Without each of you this project would not have been possible. I thank you for your time, effort, and feedback in working with me.

4 Responses to “ACL Reconstruction, Rehabilitation and Return to Play”

Mike Gross

Kyle- excellent work on all of this. The paper, power point and evidence tables were great and provide valuable resources for you and Angela and anyone else who chooses to take advantage of your fine work. i hope this project turned out to be everything you wanted it to be in terms of your own learning objectives. Mike Gross

alauten

Hey Matt!

Thank you so much for your kind words regarding our project! I think Kyle answered your question very well, but I think he and I both have a better appreciation for the impact on and healing of tissues in an injury/surgery like this. I think you (too), having had the Advanced Orthopaedic Assessment class in the fall, probably have a better appreciation for the tissues as well. Something I learned throughout this whole process (and really the reason I wanted to combine efforts with Kyle) is that you can’t look at early rehab vs later rehab (return-to-sports) as separate entities – both have an impact on the other, and both matter for the safety of and most efficient intervention for the individual (athlete or not).

I hope you will be able to use some of our information in your future clinical experiences! Please feel free to!

Thanks again!

Kyle Hoppes

Matt,

Thank you for reviewing our information and providing questions about rehabilitation. Unfortunately, the research doesn’t focus on elite athletes due to the amount invested in them. Most of the literature used “athletic” populations, typically with a mean age in the 20s. From what I have read and from the information I gained at CSM, accelerated protocols are phasing out. Accelerated rehabilitation as defined in the literature was not much faster than what I would consider “normal”. Most programs were focused on return to play by 6 months at the earliest, while only about 2 studies have shown return to play in programs lasting 90-120 days (3-4 months). I would caution you on return to play for athletes this early due to the properties of healing tissue leading to a point of weakness somewhere between 6-8 weeks.

In regards to your question about motivation, this is anecdotal evidence obtained from CSM. In two different presentations we heard there was a strong focus on psychological health of the athlete during rehabilitation. Joseph Rauch, at the University of Cincinnati, suggests that in order to keep an athlete motivated we should include them in normal strength and conditioning with their respected teams. This means if the player has as ACL injury then they should be performing the same UE exercises as their teammates. George Davies has also suggested that athletes who have a goal to get back on the field and make it to the NFL, are typically more motivated than a 2nd or 3rd string player.

Lastly, in my own ACL rehabilitation I wish there were many things that went differently. First, my coach told me to get back into practice and when I tried to jog back out I collapsed. Second, my doctor told me that my sports career was over. This crushed me and I told myself that I wanted to get back to play basketball. He was of the philosophy that time-based progression was necessary and that I would be returned to play at 6 months. Third, I was never informed of different graft types and so I have a hamstring graft. If I had known what I know now I would have chosen a BPTB graft. Fourth, my PT was great but I never felt that I was pushed as hard as I should have been. I never performed sport specific drills or incorporated balance training. I returned to sports as soon as 6 months were up, even though I felt just as strong and stable at 5 months. I think if progression criteria had been used I may have returned sooner to athletics.

Hope this answers your questions. Feel free to ask for clarification of anything else.

Matthew Medlin

Kyle and Angela,

Kudos to you guys, this is a very expansive and controversial topic. I think you guys did an outstanding job at synthesizing which is undoubtedly a large amount of complex information. I definitely plan on working through the information and understanding the evidence behind your project more as I work with ACL patients in the future.

My question is, what differences did you find on the use of accelerated vs. nonaccelerated protocols in individuals that are “normal” and those of the elite athlete populations? I know one characteristic you describe in weighing is that of motivation, and I am just curious as to what evidence or even anecdotal support there is for say Adrian Peterson vs. Kyle Hoppes? In your own experience Kyle for you return following ACLR would there be things you wish the PT or rehab team had done differently?